Spread Betting vs. CFD Trading: Unveiling the Key Differences

For those navigating the complex world of financial trading, the terms spread betting and CFD trading often arise. Both offer avenues to speculate on the price movements of various assets, but understanding the difference between spread betting and CFD trading is crucial for making informed decisions. This article provides a comprehensive comparison, highlighting the key distinctions and helping you determine which approach best aligns with your trading goals and risk tolerance.

What is Spread Betting?

Spread betting is a form of derivative trading that allows you to speculate on the price movements of financial instruments without actually owning the underlying asset. Instead of buying or selling shares, commodities, or currencies, you’re betting on whether their price will rise or fall. The ‘spread’ refers to the difference between the buying and selling price quoted by the broker. Your profit or loss is determined by the accuracy of your prediction and the size of your stake per point movement of the asset’s price.

A key characteristic of spread betting, particularly in the UK and Ireland, is its tax-free status on profits. This is a significant advantage for many traders. However, it’s essential to remember that tax laws can change, and it’s always advisable to seek professional financial advice.

What is CFD Trading?

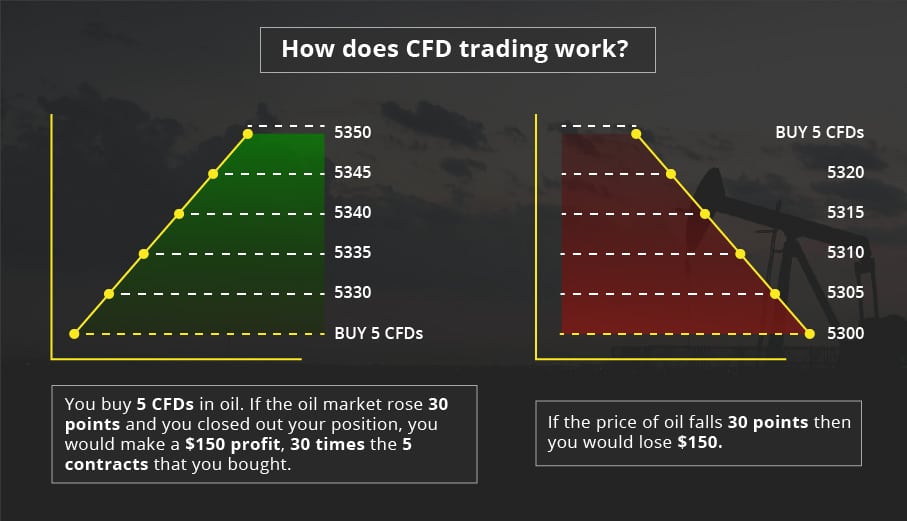

CFD trading, or Contract for Difference trading, is another form of derivative trading that allows you to speculate on the price movements of assets. Like spread betting, you don’t own the underlying asset. Instead, you enter into a contract with a broker to exchange the difference in the asset’s price between the time the contract is opened and when it’s closed.

CFDs are available on a wide range of markets, including stocks, indices, commodities, and currencies. Unlike spread betting, CFD profits are subject to capital gains tax. However, this can be offset against other capital losses, potentially offering tax advantages in certain circumstances.

Key Differences Between Spread Betting and CFD Trading

While both spread betting and CFD trading provide leveraged access to financial markets, several key differences distinguish them:

Taxation

This is arguably the most significant difference between spread betting and CFD trading. In the UK and Ireland, spread betting profits are generally exempt from capital gains tax, while CFD profits are subject to it. This tax advantage can make spread betting more attractive for some traders, especially those with larger profits.

Pricing and Spreads

The way prices are quoted can also differ. Spread betting firms typically quote a wider spread, which is their primary source of revenue. CFD brokers may offer tighter spreads but often charge commissions on each trade. Therefore, it’s essential to compare the overall cost of trading, including spreads and commissions, before choosing a platform.

Market Access

Both spread betting and CFD trading offer access to a wide range of markets. However, some brokers may specialize in specific asset classes or regions. It’s worth researching which platforms offer the markets you’re most interested in trading.

Regulation

Both spread betting and CFD trading are regulated financial activities. In the UK, they are regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). This regulation provides a level of protection for traders, ensuring that brokers adhere to certain standards and practices. However, it’s crucial to choose a reputable and regulated broker to minimize risk.

Leverage

Both spread betting and CFD trading offer leveraged trading. Leverage allows you to control a large position with a relatively small amount of capital. While leverage can amplify profits, it can also magnify losses. It’s crucial to understand the risks associated with leverage before using it.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Spread Betting Advantages

- Tax-free profits (in the UK and Ireland)

- Simplified trading

- Fixed risk per point movement

Spread Betting Disadvantages

- Wider spreads

- Potential for significant losses with leverage

- Availability may be limited in some regions

CFD Trading Advantages

- Tighter spreads (potentially)

- Access to a wider range of markets

- Offsetting capital losses against profits

CFD Trading Disadvantages

- Subject to capital gains tax

- Commissions may apply

- Potential for significant losses with leverage

Choosing the Right Option

The best choice between spread betting and CFD trading depends on your individual circumstances and trading preferences. Consider the following factors:

- Tax situation: If you’re in the UK or Ireland and want to avoid capital gains tax, spread betting may be more appealing.

- Trading style: If you prefer a simpler trading experience with fixed risk per point, spread betting may be suitable.

- Market access: Ensure the platform offers the markets you want to trade.

- Cost: Compare spreads, commissions, and other fees.

- Risk tolerance: Understand the risks associated with leverage and choose a platform that aligns with your risk appetite.

Examples of Spread Betting and CFD Trading

Let’s illustrate the difference between spread betting and CFD trading with examples.

Spread Betting Example: You believe the price of a stock currently trading at 100 will increase. You place a spread bet, buying at 101 (the broker’s offer price) at £10 per point. If the price rises to 110, you profit £90 (£10 per point x 9 points). However, if the price falls to 90, you lose £110 (£10 per point x 11 points).

CFD Trading Example: You believe the price of the same stock will increase. You buy a CFD at 100. The broker charges a small commission. If the price rises to 110, you sell the CFD, making a profit of £10 per share, minus the commission. If the price falls to 90, you sell the CFD, incurring a loss of £10 per share, plus the commission.

The Impact of Leverage on Trading Outcomes

Leverage is a double-edged sword. It allows traders to control larger positions with less capital, potentially amplifying profits. However, it also magnifies losses. Understanding how leverage works is essential for both spread betting and CFD trading. For example, if you use 10:1 leverage, a 1% price movement in your favor results in a 10% profit on your invested capital. Conversely, a 1% price movement against you results in a 10% loss. Responsible leverage management is crucial for protecting your capital. [See also: Understanding Leverage in Forex Trading]

Risk Management Strategies

Effective risk management is paramount in both spread betting and CFD trading. Here are some strategies to consider:

- Stop-loss orders: Automatically close your position if the price moves against you beyond a predetermined level.

- Limit orders: Automatically close your position when the price reaches a desired profit target.

- Position sizing: Carefully determine the size of your trades based on your risk tolerance and account balance.

- Diversification: Spread your risk across different markets and asset classes.

- Education: Continuously learn and improve your trading knowledge and skills.

The Future of Spread Betting and CFD Trading

Spread betting and CFD trading continue to evolve with technological advancements and regulatory changes. The increasing accessibility of online trading platforms and the growing demand for leveraged products are driving the popularity of these instruments. However, regulatory bodies are also focusing on investor protection, implementing measures to limit leverage and enhance transparency. Staying informed about these developments is crucial for traders.

Conclusion: Making an Informed Decision

Understanding the difference between spread betting and CFD trading is essential for anyone considering trading these instruments. While both offer leveraged access to financial markets, the tax implications, pricing structures, and other factors can significantly impact your trading outcomes. By carefully considering your individual circumstances, trading goals, and risk tolerance, you can choose the option that best suits your needs. Remember to always trade responsibly and seek professional financial advice if needed. The key is to understand the nuances and make an informed decision based on your specific circumstances. Remember, both spread betting and CFD trading come with inherent risks, and it’s vital to have a solid understanding of these risks before engaging in any trading activity. Always conduct thorough research and consider seeking advice from a qualified financial advisor.