Unraveling the Theory of Liquidity Preference: A Comprehensive Guide

In the realm of macroeconomics, understanding the forces that drive interest rates is crucial for grasping the overall health and direction of an economy. One of the key theories explaining these dynamics is the theory of liquidity preference. Developed by the renowned economist John Maynard Keynes, the theory of liquidity preference posits that the interest rate is determined by the supply and demand for money. This article delves into the intricacies of this theory, exploring its underlying principles, assumptions, and implications for economic policy.

What is the Theory of Liquidity Preference?

At its core, the theory of liquidity preference asserts that individuals and businesses hold money for various reasons, including transactions, precautionary measures, and speculation. The demand for money, therefore, is a reflection of these motivations. On the other hand, the supply of money is largely controlled by the central bank, such as the Federal Reserve in the United States or the European Central Bank in the Eurozone. The equilibrium interest rate, according to this theory, is the point where the demand for money equals the supply of money.

Keynes argued that the interest rate is a purely monetary phenomenon, meaning it is determined in the market for money rather than in the market for loanable funds, which is the traditional classical view. This distinction is critical because it highlights the role of monetary policy in influencing interest rates and, consequently, economic activity. The theory of liquidity preference offers a framework for understanding how changes in the money supply or shifts in the demand for money can impact interest rates and, by extension, investment, consumption, and overall economic growth.

The Three Motives for Holding Money

Keynes identified three primary motives for holding money, each contributing to the overall demand for liquidity:

- Transactions Motive: This is the most straightforward motive. People need money to conduct everyday transactions, such as buying groceries, paying bills, and making purchases. The amount of money held for transactions is directly related to the level of income. Higher income generally leads to more spending and, therefore, a greater demand for money for transactions.

- Precautionary Motive: Individuals and businesses hold money as a buffer against unexpected expenses or unforeseen circumstances. This “rainy day fund” provides a sense of security and allows for flexibility in dealing with emergencies. The precautionary demand for money is influenced by factors such as risk aversion and the perceived likelihood of unexpected events.

- Speculative Motive: This is the most interesting and controversial motive. Keynes argued that people hold money as an asset, anticipating future changes in interest rates or asset prices. If individuals expect interest rates to rise, they may hold onto money now, hoping to invest it later at a higher yield. Conversely, if they expect interest rates to fall, they may be more inclined to invest their money now, before rates decline further. This speculative demand for money is inversely related to the interest rate; higher interest rates reduce the demand for money, while lower interest rates increase it.

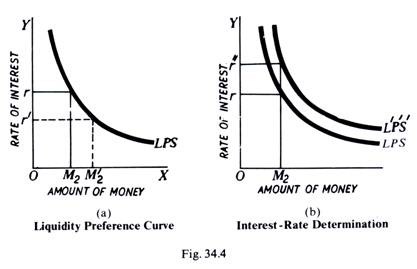

The Demand for Money Curve

The demand for money curve illustrates the relationship between the interest rate and the quantity of money demanded. According to the theory of liquidity preference, this curve slopes downward. This is because, as the interest rate rises, the opportunity cost of holding money increases. When interest rates are high, individuals are more likely to invest their money in interest-bearing assets, such as bonds or savings accounts, rather than holding onto cash. Conversely, when interest rates are low, the opportunity cost of holding money is lower, and individuals are more willing to hold onto cash.

The position of the demand for money curve can shift due to changes in factors other than the interest rate. For example, an increase in income would likely shift the demand curve to the right, as people would need more money for transactions. Similarly, an increase in uncertainty about the future could shift the demand curve to the right, as people would want to hold more money for precautionary reasons.

The Supply of Money Curve

The supply of money curve represents the total amount of money available in the economy. This is largely determined by the central bank through various monetary policy tools, such as setting reserve requirements, adjusting the discount rate, and conducting open market operations. In the theory of liquidity preference, the supply of money curve is typically depicted as a vertical line. This reflects the assumption that the central bank can control the money supply independently of the interest rate. In reality, the central bank’s control over the money supply is not perfect, and the supply curve may have a slight upward slope.

Equilibrium in the Money Market

The equilibrium interest rate is determined by the intersection of the demand for money curve and the supply of money curve. At this point, the quantity of money demanded equals the quantity of money supplied. If the interest rate is above the equilibrium level, there will be an excess supply of money, putting downward pressure on interest rates. Conversely, if the interest rate is below the equilibrium level, there will be an excess demand for money, putting upward pressure on interest rates. The market forces of supply and demand will push the interest rate towards the equilibrium level.

Implications for Monetary Policy

The theory of liquidity preference has significant implications for monetary policy. According to this theory, the central bank can influence interest rates by changing the money supply. An increase in the money supply will shift the supply of money curve to the right, leading to a lower equilibrium interest rate. Conversely, a decrease in the money supply will shift the supply of money curve to the left, leading to a higher equilibrium interest rate.

Lower interest rates can stimulate economic activity by encouraging investment and consumption. Businesses are more likely to invest in new projects when borrowing costs are low, and consumers are more likely to make purchases when interest rates on loans and credit cards are low. Higher interest rates, on the other hand, can dampen economic activity by making borrowing more expensive and discouraging investment and consumption. The theory of liquidity preference suggests that monetary policy can be a powerful tool for influencing economic growth and inflation.

However, the effectiveness of monetary policy can be influenced by factors such as the sensitivity of investment and consumption to changes in interest rates, the credibility of the central bank, and the expectations of economic actors. For example, if businesses and consumers are pessimistic about the future, they may be reluctant to borrow and spend, even if interest rates are low. In such cases, monetary policy may be less effective in stimulating economic activity. [See also: Fiscal Policy and Economic Growth]

Limitations of the Theory of Liquidity Preference

While the theory of liquidity preference provides a valuable framework for understanding the relationship between money, interest rates, and economic activity, it is not without its limitations. One criticism is that it oversimplifies the financial system and the factors that influence interest rates. In reality, interest rates are affected by a wide range of factors, including inflation expectations, government debt, and global capital flows.

Another limitation is that the theory of liquidity preference assumes that the central bank has complete control over the money supply. In practice, the central bank’s control is imperfect, and the money supply can be influenced by factors such as bank lending and currency flows. Furthermore, the theory does not fully account for the role of credit markets and the availability of credit in influencing economic activity.

Despite these limitations, the theory of liquidity preference remains a valuable tool for economists and policymakers. It provides a useful framework for understanding the forces that drive interest rates and the potential impact of monetary policy on the economy. By understanding the principles of the theory of liquidity preference, individuals can gain a deeper appreciation for the complex workings of the financial system and the challenges faced by policymakers in managing the economy. [See also: Understanding Inflation]

The Role of Expectations

Expectations play a crucial role in the theory of liquidity preference, particularly concerning the speculative motive for holding money. If individuals expect interest rates to rise in the future, they are more likely to hold onto money now, hoping to invest it later at a higher yield. This increased demand for money can put upward pressure on current interest rates.

Conversely, if individuals expect interest rates to fall, they are more likely to invest their money now, before rates decline further. This decreased demand for money can put downward pressure on current interest rates. Therefore, central banks often try to manage expectations through communication and signaling, attempting to guide market participants’ beliefs about future monetary policy decisions. [See also: Central Banking in the 21st Century]

Real-World Applications

The theory of liquidity preference is not just an academic concept; it has real-world applications for understanding and responding to economic events. For example, during times of economic uncertainty, such as a financial crisis or a recession, the demand for money often increases as individuals and businesses become more risk-averse and seek the safety of cash. This increased demand for money can push interest rates higher, potentially exacerbating the economic downturn.

In response, central banks may implement expansionary monetary policies, such as lowering interest rates or increasing the money supply, to counteract the increased demand for money and stimulate economic activity. The effectiveness of these policies depends on various factors, including the credibility of the central bank and the degree to which economic actors respond to changes in interest rates. [See also: The Great Recession of 2008]

Conclusion

The theory of liquidity preference provides a valuable framework for understanding the relationship between money, interest rates, and economic activity. While it has limitations, it remains a cornerstone of macroeconomic theory and a useful tool for policymakers. By understanding the principles of this theory, individuals can gain a deeper appreciation for the complex workings of the financial system and the challenges faced by policymakers in managing the economy. The theory of liquidity preference underscores the importance of monetary policy in influencing interest rates and, consequently, investment, consumption, and overall economic growth. As the global economy continues to evolve, understanding the nuances of this theory will remain crucial for navigating the complexities of the financial landscape.