Deflation Explained: Understanding Its Causes, Consequences, and Cures

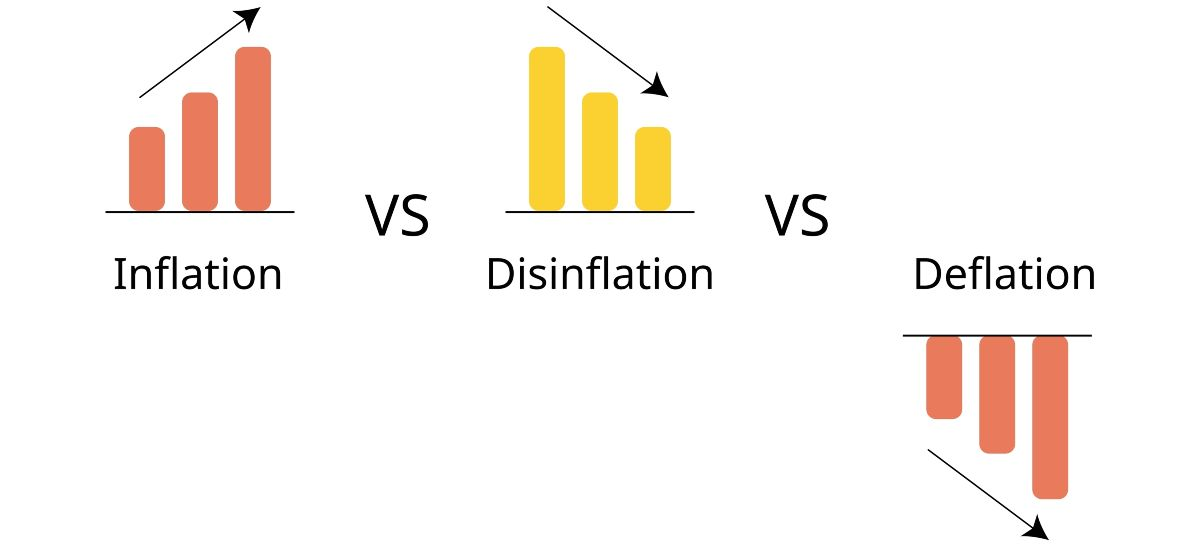

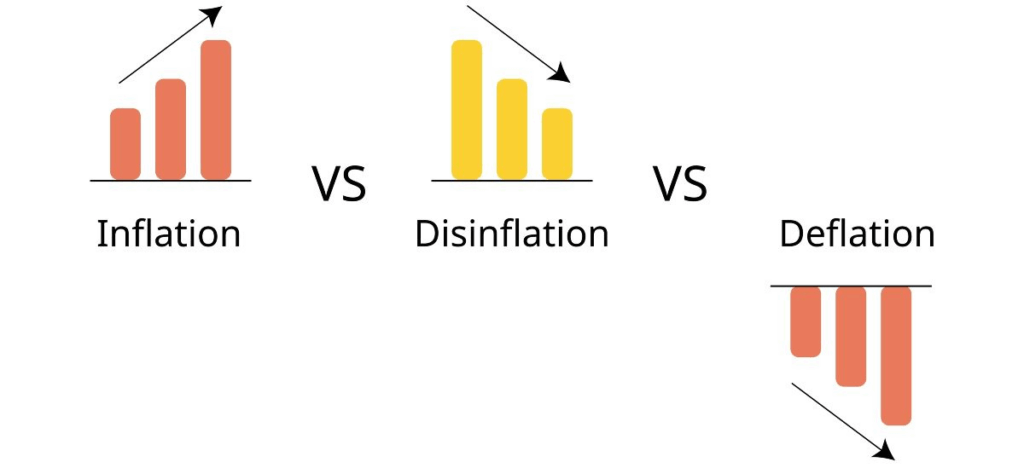

Deflation, the opposite of inflation, is a sustained decrease in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. While it might sound appealing at first – who wouldn’t want things to cost less? – deflation can actually be a sign of deeper economic problems. This article will delve into what deflation is, its causes, the potentially damaging consequences, and the measures economists and policymakers can take to combat it.

What is Deflation? A Closer Look

At its core, deflation signifies that the purchasing power of money is increasing. This means you can buy more goods and services with the same amount of money than you could before. While a temporary dip in prices might occur due to seasonal factors or sales, deflation is characterized by a prolonged and widespread decline in prices across the economy. This distinction is crucial; a single industry experiencing lower prices isn’t necessarily deflation, but when multiple sectors see sustained price drops, it signals a broader economic phenomenon.

Causes of Deflation: Unraveling the Roots

Several factors can trigger deflation, often intertwined and reinforcing each other. Understanding these causes is essential for developing effective countermeasures.

Decreased Aggregate Demand

One of the most common causes of deflation is a significant drop in aggregate demand – the total demand for goods and services in an economy. This can be triggered by various events, such as:

- Recessions: Economic downturns often lead to reduced consumer spending and business investment, leading to lower demand and, consequently, lower prices.

- Increased Savings: If consumers become overly cautious and start saving a larger portion of their income, the reduced spending can decrease demand and contribute to deflation.

- Government Austerity Measures: When governments cut spending to reduce budget deficits, it can dampen aggregate demand and put downward pressure on prices.

Increased Aggregate Supply

Conversely, a sudden and substantial increase in aggregate supply – the total amount of goods and services available in an economy – can also lead to deflation. This can occur due to:

- Technological Advancements: Innovations that significantly boost productivity can lead to a surplus of goods, driving prices down.

- Increased Competition: The entry of new competitors into a market can increase supply and intensify price competition.

- Lower Input Costs: If the cost of raw materials, labor, or energy decreases substantially, businesses might lower prices to attract more customers.

The Role of Money Supply

A contraction in the money supply – the total amount of money circulating in an economy – can also contribute to deflation. When there’s less money available, demand tends to decrease, leading to lower prices. This can happen when central banks tighten monetary policy by raising interest rates or reducing the amount of money they inject into the economy.

Debt Deflation

Economist Irving Fisher introduced the theory of debt deflation to explain the Great Depression. This theory suggests that high levels of debt combined with deflation can create a vicious cycle. As prices fall, the real value of debt increases, making it more difficult for borrowers to repay their loans. This can lead to defaults, foreclosures, and further economic contraction, exacerbating the deflationary spiral. [See also: Understanding Debt Cycles]

Consequences of Deflation: Why It’s Not Always a Good Thing

While lower prices might seem beneficial, deflation can have several negative consequences for an economy.

Delayed Spending

One of the most significant problems with deflation is that it encourages consumers and businesses to delay spending. If they expect prices to be even lower in the future, they’ll postpone purchases, hoping to get a better deal later. This reduced spending further weakens demand and reinforces the deflationary trend.

Increased Real Debt Burden

As mentioned earlier, deflation increases the real value of debt. This means that borrowers have to repay their loans with money that is worth more than when they initially borrowed it. This can strain household budgets and business finances, leading to defaults and bankruptcies.

Reduced Investment

Deflation can discourage investment. Businesses may be hesitant to invest in new projects if they expect prices to fall, reducing their potential profits. This lack of investment can stifle economic growth and innovation.

Wage Cuts

In a deflationary environment, businesses may face pressure to cut wages to maintain profitability. Wage cuts can lead to lower consumer spending and further depress demand, contributing to the deflationary spiral.

Increased Real Interest Rates

Even if nominal interest rates (the stated interest rate on a loan) are low, deflation can increase real interest rates (the nominal interest rate minus the inflation rate). High real interest rates can discourage borrowing and investment, further dampening economic activity.

Cures for Deflation: Fighting Back Against Falling Prices

Combating deflation requires a multi-pronged approach that addresses both the demand and supply sides of the economy.

Monetary Policy

Central banks play a crucial role in fighting deflation. They can use monetary policy tools to stimulate demand and increase the money supply.

- Lowering Interest Rates: Reducing interest rates makes borrowing cheaper, encouraging consumers and businesses to spend and invest.

- Quantitative Easing (QE): This involves a central bank injecting money into the economy by purchasing assets, such as government bonds. QE aims to lower long-term interest rates and increase liquidity.

- Negative Interest Rates: Some central banks have experimented with negative interest rates on commercial banks’ reserves held at the central bank. This aims to incentivize banks to lend more money.

Fiscal Policy

Governments can also use fiscal policy to combat deflation by increasing government spending or cutting taxes. [See also: Fiscal Stimulus Packages]

- Increased Government Spending: Investing in infrastructure projects, education, or other public goods can boost demand and create jobs.

- Tax Cuts: Reducing taxes can increase disposable income, encouraging consumers to spend more.

Managing Expectations

Central banks and governments also need to manage expectations. If people believe that deflation will persist, they are more likely to delay spending, making the problem worse. Clear communication and credible policy commitments can help to anchor expectations and prevent a deflationary spiral.

Addressing Debt

Dealing with high levels of debt is crucial for overcoming deflation. Governments can implement policies to help borrowers manage their debt burden, such as debt restructuring programs or mortgage relief initiatives.

Examples of Deflation in History

Deflation isn’t just a theoretical concept; it has occurred in various countries throughout history. The most notable example is the Great Depression of the 1930s, which saw widespread deflation, unemployment, and economic hardship. Japan also experienced a prolonged period of deflation in the 1990s and 2000s, known as the Lost Decade.

Conclusion: Understanding and Addressing Deflation

Deflation, while seemingly beneficial on the surface, can be a dangerous economic phenomenon. It can lead to delayed spending, increased debt burdens, reduced investment, and wage cuts, ultimately hindering economic growth. Understanding the causes and consequences of deflation is crucial for policymakers and individuals alike. By implementing appropriate monetary and fiscal policies, managing expectations, and addressing debt issues, economies can effectively combat deflation and promote sustainable growth. The key is proactive intervention and a comprehensive strategy to prevent a deflationary spiral from taking hold.