Deflation in the Economy: Understanding Its Causes, Consequences, and Potential Solutions

Deflation, the persistent decrease in the general price level of goods and services in an economy, is often perceived as the opposite of inflation. While seemingly beneficial on the surface – as goods become cheaper – deflation can have detrimental effects on economic growth and stability. This article delves into the complexities of deflation in the economy, exploring its causes, consequences, and potential solutions.

What is Deflation?

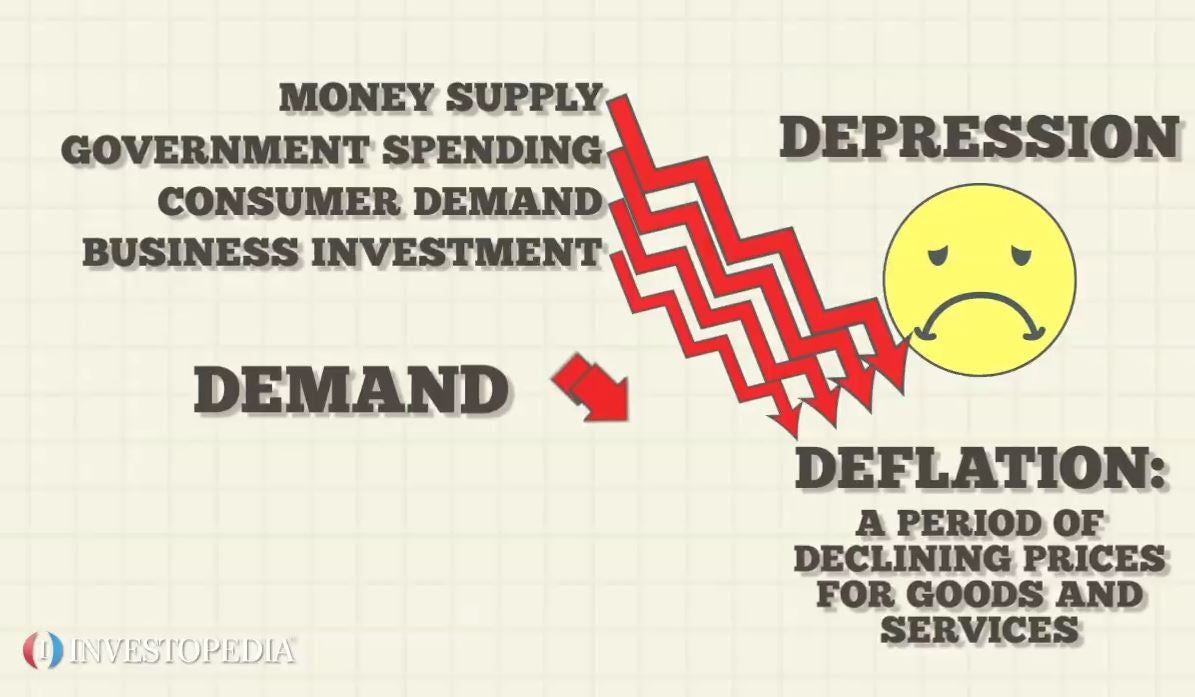

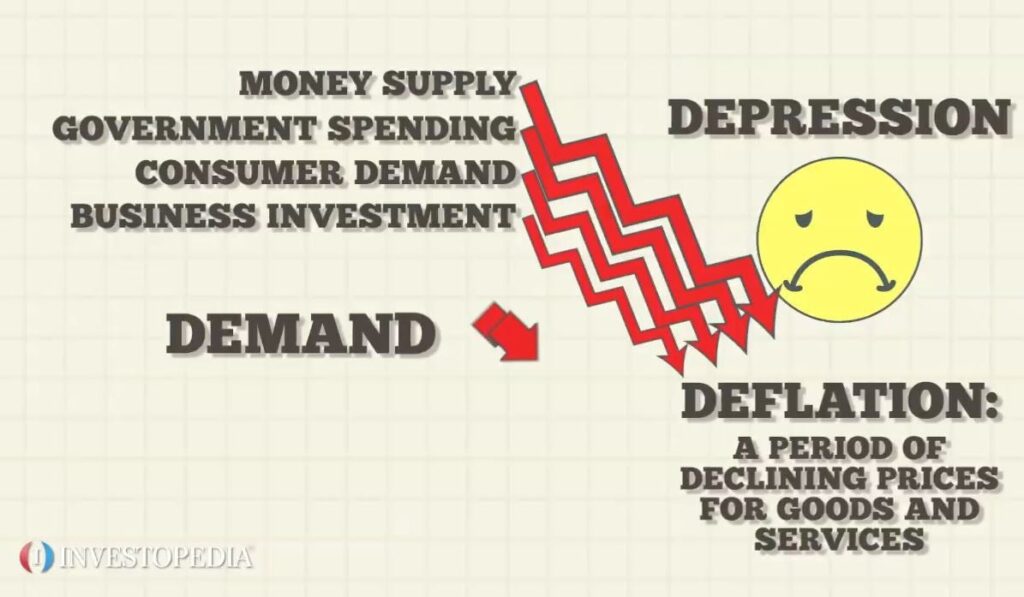

Deflation occurs when the inflation rate falls below 0%, meaning that prices are declining. This is different from disinflation, which is a slowdown in the rate of inflation. Deflation can be caused by various factors, including a decrease in aggregate demand, an increase in aggregate supply, or a combination of both. Understanding the root cause is crucial for implementing effective policy responses. The concept of deflation is often misunderstood; it’s not simply about lower prices, but about a sustained and generalized decline in the price level across the economy.

Causes of Deflation

Several factors can trigger deflation. Understanding these causes is essential for policymakers to implement appropriate counter-measures.

Decreased Aggregate Demand

A significant drop in consumer spending and investment can lead to deflation. This can be triggered by economic recessions, high unemployment rates, or a loss of consumer confidence. When demand falls, businesses are forced to lower prices to attract customers, leading to a downward spiral.

Increased Aggregate Supply

Technological advancements and increased productivity can lead to a surge in the supply of goods and services. If demand does not keep pace with this increased supply, prices will fall, resulting in deflation. This is often referred to as “good deflation,” as it is driven by increased efficiency and productivity.

Debt and Leverage

High levels of debt can exacerbate deflation. As prices fall, the real value of debt increases, making it more difficult for individuals and businesses to repay their loans. This can lead to defaults and further contraction of the economy.

Monetary Policy

Contractionary monetary policies, such as raising interest rates or reducing the money supply, can also contribute to deflation. These policies are typically implemented to combat inflation, but if applied too aggressively, they can stifle economic growth and lead to falling prices.

Consequences of Deflation

While lower prices may seem appealing, deflation can have several adverse consequences for the economy.

Delayed Consumption

When consumers expect prices to fall further, they may delay purchases, hoping to buy goods and services at even lower prices in the future. This postponement of spending reduces aggregate demand and further exacerbates deflation. This creates a vicious cycle where the expectation of lower prices leads to lower demand, which in turn leads to even lower prices.

Increased Real Debt Burden

As mentioned earlier, deflation increases the real value of debt. This can make it more difficult for individuals and businesses to repay their loans, leading to defaults and financial distress. This increased debt burden can further dampen economic activity.

Reduced Investment

Deflation can discourage investment as businesses anticipate lower profits due to falling prices. This reduced investment can lead to lower economic growth and higher unemployment rates. Companies become hesitant to expand or undertake new projects when they foresee declining revenues.

Wage Cuts and Unemployment

Businesses facing falling prices may be forced to cut wages or lay off workers to maintain profitability. This can lead to a decrease in consumer spending and further exacerbate deflation. The combination of wage cuts and unemployment creates a significant drag on economic activity.

Difficulty for Central Banks

Deflation can limit the effectiveness of monetary policy. Central banks typically lower interest rates to stimulate economic activity. However, when interest rates are already near zero (the “zero lower bound”), it becomes difficult to further stimulate the economy through monetary policy. This situation is known as a liquidity trap.

Examples of Deflationary Periods

Several historical periods have been marked by deflation, providing valuable insights into its causes and consequences.

The Great Depression (1930s)

The Great Depression was characterized by severe deflation, high unemployment, and a sharp decline in economic activity. A combination of factors, including the stock market crash of 1929 and contractionary monetary policies, contributed to the deflationary spiral.

Japan in the 1990s and 2000s

Japan experienced a prolonged period of deflation in the 1990s and 2000s, often referred to as the “Lost Decade.” This was caused by a combination of factors, including the bursting of an asset bubble in the late 1980s and ineffective policy responses. [See also: Japan’s Economic Stagnation]

Potential Solutions to Deflation

Addressing deflation requires a multi-faceted approach involving both monetary and fiscal policies.

Monetary Policy

Central banks can implement expansionary monetary policies to combat deflation. This includes lowering interest rates, increasing the money supply, and implementing quantitative easing (QE). QE involves the central bank purchasing assets to inject liquidity into the financial system. However, as mentioned earlier, the effectiveness of monetary policy can be limited when interest rates are near zero.

Fiscal Policy

Governments can use fiscal policy to stimulate aggregate demand and combat deflation. This includes increasing government spending, cutting taxes, and implementing infrastructure projects. Fiscal stimulus can directly boost economic activity and help to reverse the deflationary trend. [See also: Fiscal Stimulus Packages]

Structural Reforms

Structural reforms aimed at increasing productivity and competitiveness can also help to combat deflation. This includes deregulation, investment in education and training, and measures to promote innovation. These reforms can boost long-term economic growth and reduce the risk of deflation.

Inflation Targeting

Many central banks use inflation targeting as a tool to manage inflation. Some economists argue that adopting a higher inflation target can help to prevent deflation. A higher inflation target provides a buffer against falling prices and gives the central bank more room to maneuver during economic downturns.

The Debate Around Deflation

While most economists agree that prolonged deflation can be harmful, there is some debate about the severity of its effects. Some argue that “good deflation,” driven by increased productivity, can be beneficial for consumers. However, even “good deflation” can pose challenges for policymakers if it leads to a decrease in aggregate demand. The key is to differentiate between deflation caused by supply-side improvements and deflation resulting from demand-side weakness.

Conclusion

Deflation in the economy is a complex phenomenon with potentially serious consequences. Understanding its causes, consequences, and potential solutions is crucial for policymakers to maintain economic stability. While lower prices may seem appealing on the surface, prolonged deflation can lead to a vicious cycle of declining demand, increased debt burdens, and reduced investment. A combination of monetary and fiscal policies, along with structural reforms, is necessary to effectively combat deflation and promote sustainable economic growth. Successfully navigating the challenges of deflation requires a proactive and well-coordinated approach from both central banks and governments. Preventing deflation is often easier than reversing it once it has taken hold, highlighting the importance of early intervention and vigilance. The nuanced understanding of deflation remains critical for economic stability.