Understanding the Liquidity Preference Theory: A Comprehensive Guide

The liquidity preference theory, a cornerstone of Keynesian economics, explains how interest rates are determined by the supply and demand for money. Introduced by John Maynard Keynes in his seminal work, “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money,” this theory posits that individuals prefer to hold their wealth in the most liquid form – money – rather than investing in less liquid assets like bonds or stocks. This preference for liquidity influences the level of interest rates in an economy. Understanding the nuances of the liquidity preference theory is crucial for grasping the dynamics of monetary policy and its impact on economic activity.

Key Concepts of Liquidity Preference Theory

At its core, the liquidity preference theory rests on three primary motives that drive individuals’ demand for money:

- Transaction Motive: This is the most basic motive. People need money to conduct everyday transactions, such as buying groceries, paying bills, and making other routine purchases. The amount of money demanded for transactional purposes is directly related to the level of income. As income rises, so does the demand for money to facilitate increased spending.

- Precautionary Motive: Individuals and businesses hold money as a buffer against unexpected expenses or opportunities. This precautionary demand for money is influenced by factors such as uncertainty about future income, potential medical emergencies, or unforeseen business setbacks. The higher the perceived risk and uncertainty, the greater the precautionary demand for money.

- Speculative Motive: This is the most distinctive aspect of Keynes’s theory. People hold money speculatively when they believe that other assets, such as bonds, are likely to decline in value. In other words, they prefer to hold cash and wait for a more favorable opportunity to invest. This speculative demand for money is inversely related to interest rates. When interest rates are high, the opportunity cost of holding cash is also high, so people are more likely to invest in bonds. Conversely, when interest rates are low, the opportunity cost of holding cash is low, and people are more likely to hold money speculatively.

The Demand for Money Curve

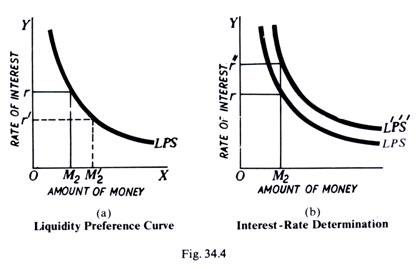

The aggregate demand for money, according to the liquidity preference theory, is the sum of the transactional, precautionary, and speculative demands. This demand is typically represented graphically as a downward-sloping curve. The x-axis represents the quantity of money, and the y-axis represents the interest rate. The downward slope reflects the inverse relationship between the interest rate and the speculative demand for money. As interest rates fall, the demand for money increases, and vice versa.

The Supply of Money

The supply of money is determined by the central bank, such as the Federal Reserve in the United States. The central bank controls the money supply through various tools, including open market operations, reserve requirements, and the discount rate. For simplicity, the money supply is often assumed to be fixed and independent of the interest rate, represented by a vertical line on the money market graph.

Equilibrium Interest Rate

The equilibrium interest rate is determined by the intersection of the demand for money curve and the supply of money curve. At this point, the quantity of money demanded equals the quantity of money supplied. If the interest rate is above the equilibrium level, there will be an excess supply of money, leading individuals and businesses to invest their excess cash, driving interest rates down. Conversely, if the interest rate is below the equilibrium level, there will be an excess demand for money, leading individuals and businesses to sell assets to obtain cash, driving interest rates up. Thus, the market naturally gravitates towards the equilibrium interest rate.

Factors Affecting Liquidity Preference

Several factors can shift the demand for money curve and influence the equilibrium interest rate:

- Changes in Income: An increase in income will increase the transactional demand for money, shifting the demand curve to the right and raising the equilibrium interest rate. Conversely, a decrease in income will decrease the transactional demand for money, shifting the demand curve to the left and lowering the equilibrium interest rate.

- Changes in Price Level: An increase in the price level will also increase the transactional demand for money, as more money is needed to purchase the same goods and services. This will shift the demand curve to the right and raise the equilibrium interest rate. A decrease in the price level will have the opposite effect.

- Changes in Expectations: Expectations about future interest rates and economic conditions can significantly impact the speculative demand for money. If people expect interest rates to rise in the future, they may hold more money speculatively, shifting the demand curve to the right and putting upward pressure on current interest rates. Conversely, if people expect interest rates to fall, they may reduce their speculative demand for money, shifting the demand curve to the left and putting downward pressure on current interest rates.

- Technological Innovations: Advances in technology, such as online banking and mobile payment systems, can reduce the demand for money by making it easier and more convenient to conduct transactions. This will shift the demand curve to the left and lower the equilibrium interest rate.

Monetary Policy and Liquidity Preference

The liquidity preference theory provides a framework for understanding how monetary policy affects interest rates and the economy. By controlling the money supply, the central bank can influence the equilibrium interest rate and, in turn, affect investment, consumption, and overall economic activity. For example, if the central bank wants to stimulate the economy, it can increase the money supply, shifting the supply curve to the right and lowering the equilibrium interest rate. This will make it cheaper for businesses to borrow money and invest, and for consumers to borrow money and spend, leading to increased economic activity. [See also: How Central Banks Control Inflation]

Conversely, if the central bank wants to curb inflation, it can decrease the money supply, shifting the supply curve to the left and raising the equilibrium interest rate. This will make it more expensive for businesses and consumers to borrow money, leading to decreased spending and investment, and ultimately, lower inflation. The effectiveness of monetary policy, however, can be influenced by the sensitivity of the demand for money to changes in interest rates. If the demand for money is highly sensitive to interest rates (i.e., the demand curve is relatively flat), then small changes in the money supply can have a significant impact on interest rates. Conversely, if the demand for money is relatively insensitive to interest rates (i.e., the demand curve is relatively steep), then larger changes in the money supply may be needed to achieve the desired effect on interest rates.

Limitations of the Liquidity Preference Theory

While the liquidity preference theory provides valuable insights into the determination of interest rates, it is not without its limitations. One criticism is that it overemphasizes the role of speculative demand for money and neglects other factors that can influence interest rates, such as credit risk, inflation expectations, and global capital flows. Another limitation is that the theory assumes that the money supply is exogenously determined by the central bank, which may not always be the case in practice. In reality, the money supply can also be influenced by the behavior of commercial banks and the demand for credit in the economy. Furthermore, the theory is a simplified model of a complex reality and may not fully capture the nuances of financial markets and the interactions between different economic actors.

Real-World Examples of Liquidity Preference in Action

Several real-world events illustrate the principles of the liquidity preference theory. During periods of economic uncertainty, such as the 2008 financial crisis or the COVID-19 pandemic, investors often flock to safe-haven assets like cash and government bonds, increasing the demand for liquidity and driving down interest rates. This phenomenon is known as a “flight to quality.” Similarly, during periods of rising inflation, central banks often raise interest rates to reduce the money supply and curb spending, reflecting the inverse relationship between interest rates and the demand for money described by the theory. [See also: Understanding Inflation and its Impact on Investments]

The Liquidity Trap

A specific scenario related to the liquidity preference theory is the concept of a liquidity trap. A liquidity trap occurs when interest rates are already very low, and further increases in the money supply fail to stimulate the economy because individuals and businesses simply hoard the extra cash rather than investing or spending it. In this situation, the demand for money becomes perfectly elastic, meaning that the demand curve is horizontal. Monetary policy becomes ineffective because further increases in the money supply have no impact on interest rates or economic activity. Japan experienced a liquidity trap in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and some economists believe that the United States and other developed countries may have been in a liquidity trap following the 2008 financial crisis. [See also: How Quantitative Easing Works]

Conclusion

The liquidity preference theory provides a valuable framework for understanding the factors that influence interest rates and the role of monetary policy in shaping economic activity. While the theory has its limitations, it remains a cornerstone of Keynesian economics and provides important insights into the behavior of financial markets and the dynamics of the economy. By understanding the motives behind the demand for money and the factors that can shift the demand and supply curves, policymakers can make more informed decisions about monetary policy and better manage the economy. The liquidity preference theory continues to be relevant in today’s complex economic landscape, offering valuable insights for investors, policymakers, and anyone interested in understanding the forces that shape our financial world.