Understanding the Liquidity Preference Theory: A Comprehensive Guide

In the realm of economics, understanding the motivations behind investment and saving is crucial for grasping macroeconomic trends. One such theory that attempts to explain this behavior is the liquidity preference theory. This article aims to provide a comprehensive guide to the liquidity preference theory, explaining its core concepts, implications, and criticisms. Understanding the liquidity preference theory is essential for anyone seeking to comprehend how interest rates are determined and how they influence economic activity.

What is Liquidity Preference?

At its core, liquidity preference refers to the demand for holding money in its most liquid form – cash. Individuals and businesses prefer to have immediate access to their funds for various reasons, including transactional needs, precautionary motives, and speculative opportunities. This preference influences how much they are willing to save or invest, thereby affecting interest rates. The liquidity preference theory explains why people prefer liquid assets.

The Three Motives Behind Liquidity Preference

John Maynard Keynes, the economist who formulated the liquidity preference theory, identified three primary motives driving individuals’ desire to hold liquid assets:

- Transactionary Motive: This is the most straightforward motive. People need money to conduct day-to-day transactions, such as buying groceries, paying bills, or covering business expenses. The amount of money held for transactional purposes is generally proportional to income; higher income typically leads to higher transactionary demand.

- Precautionary Motive: Life is unpredictable, and individuals and businesses often hold a buffer of cash to cover unexpected expenses or emergencies. This precautionary demand for money provides a safety net against unforeseen circumstances.

- Speculative Motive: This is where the liquidity preference theory gets particularly interesting. The speculative motive arises from the expectation that interest rates or asset prices might change in the future. If individuals anticipate that interest rates will rise, they may choose to hold onto cash now, hoping to invest later at higher rates. Conversely, if they expect asset prices to fall, they may prefer to hold cash to avoid losses.

How Liquidity Preference Determines Interest Rates

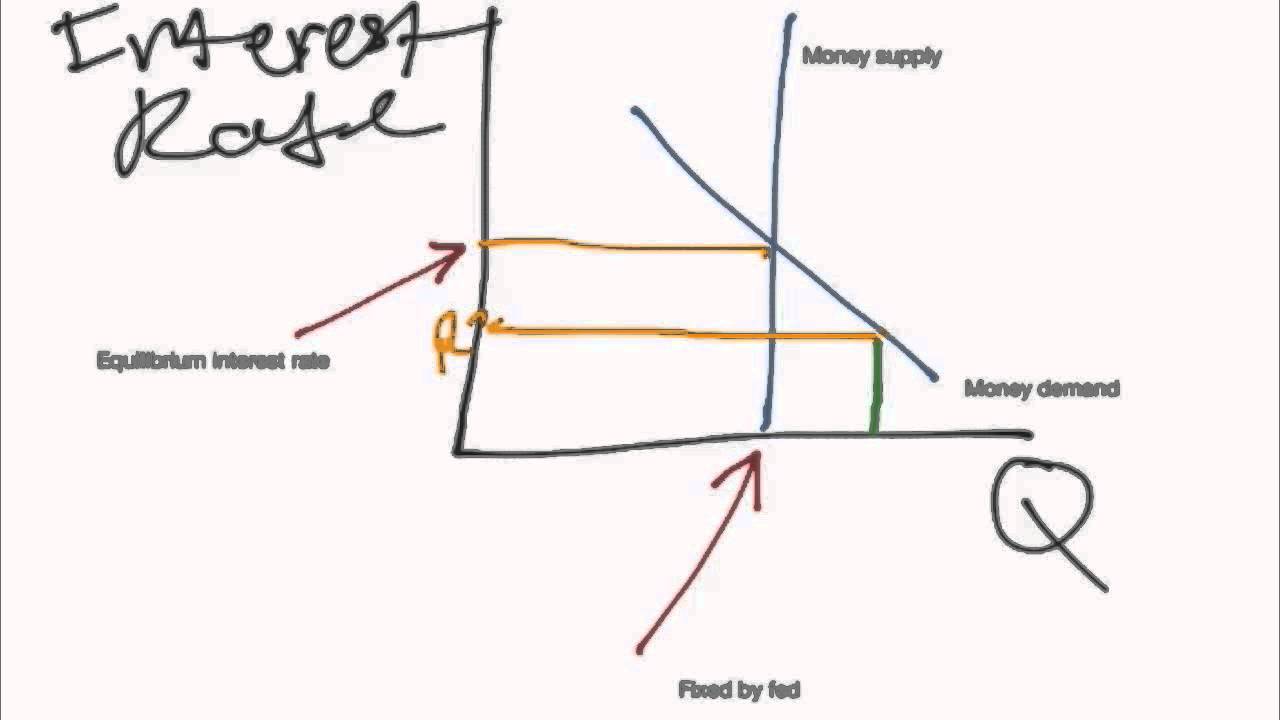

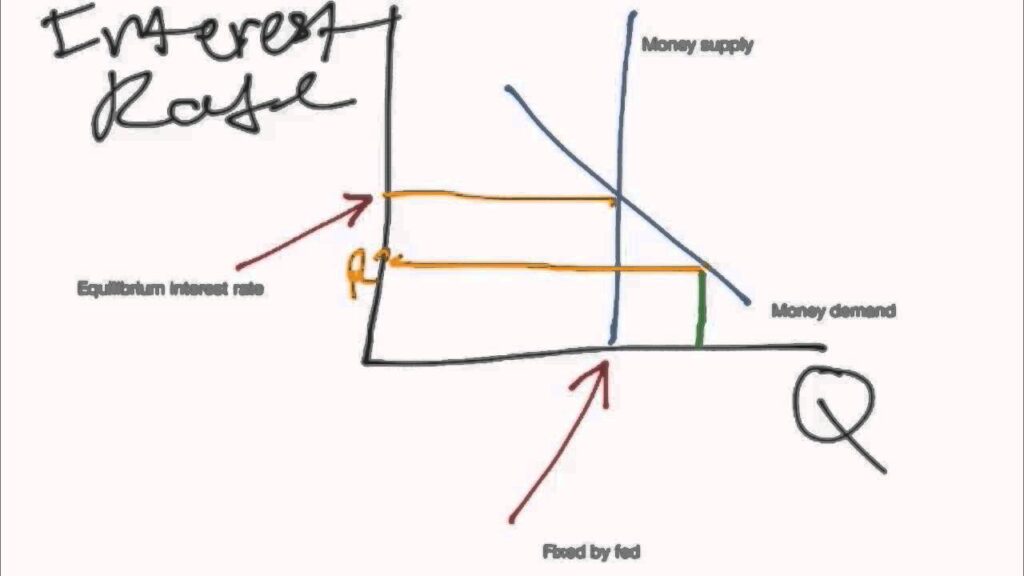

The liquidity preference theory posits that interest rates are determined by the supply and demand for money. The demand for money is essentially the aggregate liquidity preference of all individuals and businesses in the economy. The supply of money, on the other hand, is typically controlled by the central bank through monetary policy. When the demand for money exceeds the supply, interest rates tend to rise. Conversely, when the supply of money exceeds the demand, interest rates tend to fall.

The Equilibrium Interest Rate

The equilibrium interest rate is the point where the demand for money (liquidity preference) equals the supply of money. At this point, there is no pressure for interest rates to rise or fall. Central banks often use the liquidity preference theory as a framework for setting monetary policy. By adjusting the money supply, they can influence interest rates and, in turn, stimulate or restrain economic activity. For example, to combat a recession, a central bank might increase the money supply, lowering interest rates and encouraging borrowing and investment.

Implications of the Liquidity Preference Theory

The liquidity preference theory has several important implications for macroeconomic policy and economic understanding:

- Monetary Policy Effectiveness: The theory suggests that monetary policy can be an effective tool for managing the economy. By controlling the money supply, central banks can influence interest rates and stimulate or restrain economic activity.

- Interest Rate Volatility: Fluctuations in liquidity preference can lead to volatility in interest rates. Sudden increases in the demand for money, for example, can cause interest rates to spike.

- The Liquidity Trap: A potential limitation of monetary policy is the liquidity trap. This occurs when interest rates are already very low, and further increases in the money supply have little or no effect on stimulating the economy. In a liquidity trap, people simply hoard the additional money rather than investing or spending it.

Criticisms of the Liquidity Preference Theory

While the liquidity preference theory provides a valuable framework for understanding interest rate determination, it is not without its critics. Some common criticisms include:

- Oversimplification: Critics argue that the theory oversimplifies the complex factors that influence interest rates. Other factors, such as credit risk, inflation expectations, and global capital flows, can also play a significant role.

- Ignoring the Supply Side: The theory focuses primarily on the demand for money and gives less attention to the supply side. Some economists argue that the supply of loanable funds, which is influenced by savings and investment decisions, is equally important in determining interest rates.

- Empirical Evidence: Some empirical studies have questioned the empirical validity of the liquidity preference theory. The relationship between money supply, interest rates, and economic activity can be complex and difficult to isolate.

Real-World Examples of Liquidity Preference in Action

To illustrate the liquidity preference theory, consider a few real-world examples:

- Financial Crises: During financial crises, uncertainty and fear often lead to a surge in liquidity preference. Investors and businesses become risk-averse and prefer to hold cash, leading to a spike in interest rates and a contraction in lending.

- Central Bank Interventions: Central banks often intervene in financial markets to manage liquidity preference. For example, during times of stress, they may inject liquidity into the banking system to ensure that banks have sufficient funds to meet their obligations.

- Seasonal Patterns: Some industries experience seasonal patterns in liquidity preference. For example, retailers may increase their cash holdings during the holiday shopping season to meet the increased demand for goods and services.

The Role of Expectations

Expectations play a crucial role in shaping liquidity preference. If individuals and businesses expect interest rates to rise in the future, they may increase their demand for money today, hoping to invest later at higher rates. Conversely, if they expect interest rates to fall, they may decrease their demand for money, preferring to invest now before rates decline. These expectations can be influenced by a variety of factors, including economic news, central bank announcements, and global events.

Liquidity Preference and Investment Decisions

The liquidity preference theory directly impacts investment decisions. Higher liquidity preference, leading to higher interest rates, can discourage investment as the cost of borrowing increases. Conversely, lower liquidity preference and lower interest rates can stimulate investment by making it cheaper to finance projects. Businesses weigh the potential return on investment against the cost of borrowing, and interest rates are a key factor in this calculation. The liquidity preference of investors and businesses will influence their investment decisions.

The Impact on Saving

Saving behavior is also influenced by liquidity preference. When interest rates are high, individuals and businesses may be more inclined to save, as they can earn a higher return on their savings. However, if liquidity preference is strong due to uncertainty or fear, individuals may prefer to hold cash rather than save, even if interest rates are relatively high. This can lead to a decrease in overall savings and investment in the economy.

Modern Interpretations and Extensions

Modern economists have extended and refined the liquidity preference theory to incorporate new insights and address some of its limitations. For example, some models now consider the role of information asymmetry and behavioral biases in shaping liquidity preference. Others have integrated the theory with models of asset pricing and financial market dynamics. These modern interpretations provide a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence interest rates and economic activity.

Conclusion

The liquidity preference theory remains a valuable tool for understanding the determination of interest rates and the motivations behind saving and investment decisions. While it has its limitations and critics, the theory provides a fundamental framework for analyzing the demand for money and its impact on the economy. By understanding the three motives behind liquidity preference – transactional, precautionary, and speculative – policymakers and investors can gain insights into how interest rates are likely to respond to changes in economic conditions and expectations. The liquidity preference theory helps to explain fluctuations in interest rates and economic activity. [See also: Monetary Policy and Interest Rates] The theory offers valuable insights for policymakers and investors alike. Furthermore, the liquidity preference theory has been refined and extended by modern economists to incorporate new insights and address some of its limitations, offering a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence interest rates and economic activity. The liquidity preference theory is a cornerstone of macroeconomic understanding.