Understanding the Theory of Liquidity Preference: A Comprehensive Guide

The theory of liquidity preference, a cornerstone of Keynesian economics, explains how interest rates are determined by the supply and demand for money. Developed by John Maynard Keynes in his seminal work, “The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money,” this theory posits that individuals and businesses prefer to hold their wealth in the form of liquid assets, such as cash, rather than illiquid assets like bonds or real estate. This preference for liquidity influences the equilibrium interest rate in the market. Understanding the nuances of the theory of liquidity preference is crucial for comprehending monetary policy, financial markets, and macroeconomic dynamics. This article delves into the core principles, implications, and criticisms of this influential economic model.

The Core Principles of Liquidity Preference

At its heart, the theory of liquidity preference revolves around the idea that people demand money for three primary reasons: transactional, precautionary, and speculative motives.

Transactional Motive

The transactional motive refers to the need to hold money to facilitate everyday transactions. Individuals and businesses require cash to purchase goods and services, pay salaries, and cover operational expenses. The amount of money demanded for transactional purposes is directly related to the level of income and economic activity. As income increases, so does the demand for money to finance increased spending.

Precautionary Motive

The precautionary motive stems from the desire to hold money as a buffer against unforeseen circumstances. Unexpected expenses, emergencies, or investment opportunities may arise, and having readily available cash provides a safety net. The level of uncertainty and risk aversion in the economy influences the strength of the precautionary motive. During times of economic instability, individuals and businesses tend to hold more cash as a precaution against potential losses.

Speculative Motive

The speculative motive is perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the theory of liquidity preference. It arises from the belief that individuals can profit from changes in interest rates and asset prices. When interest rates are low, investors may anticipate that they will rise in the future. In this scenario, they prefer to hold money rather than invest in bonds, as they expect bond prices to decline when interest rates increase. Conversely, when interest rates are high, investors may anticipate that they will fall, making bonds more attractive. The speculative demand for money is inversely related to the prevailing interest rate.

The Interaction of Money Supply and Demand

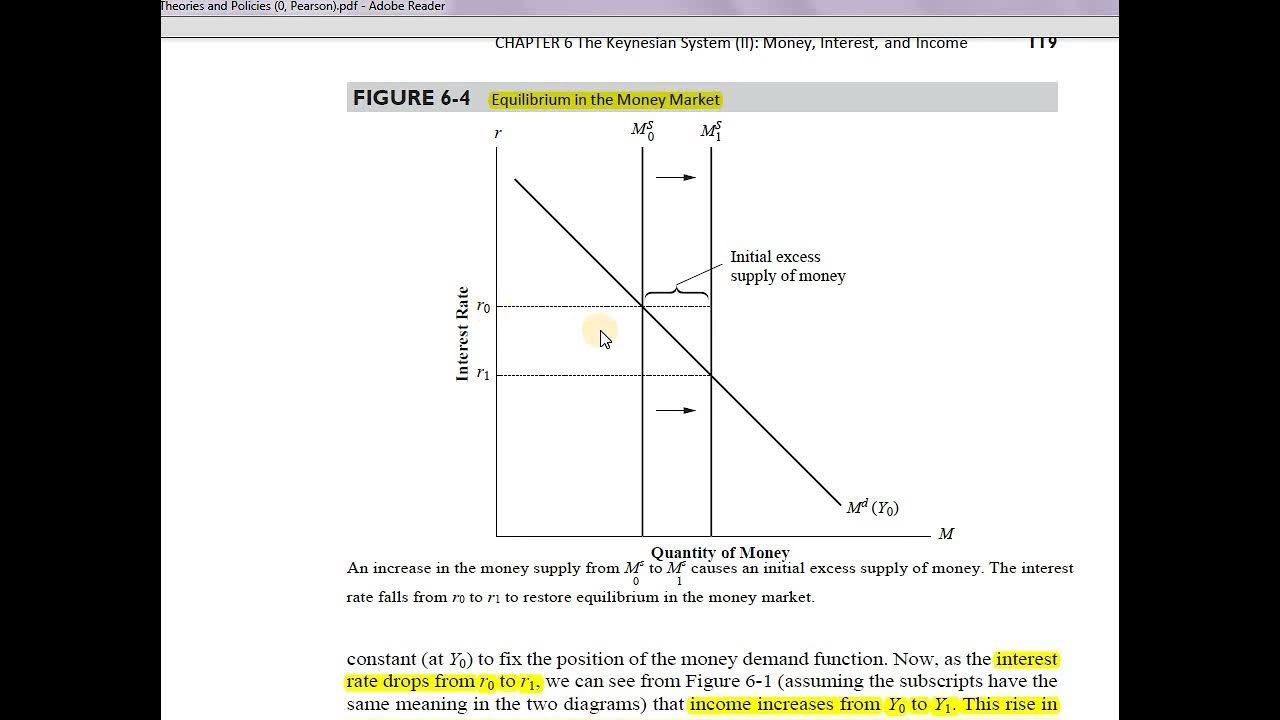

The theory of liquidity preference asserts that the equilibrium interest rate is determined by the intersection of the money supply and money demand curves. The money supply is typically controlled by the central bank, such as the Federal Reserve in the United States, and is assumed to be fixed at a given level. The money demand curve, on the other hand, represents the total demand for money at various interest rates, encompassing the transactional, precautionary, and speculative motives.

When the money supply exceeds the money demand, there is an excess supply of liquidity in the market. This surplus puts downward pressure on interest rates, as individuals and businesses seek to invest their excess cash. Conversely, when the money demand exceeds the money supply, there is a shortage of liquidity. This scarcity pushes interest rates upward, as borrowers compete for limited funds.

The central bank can influence interest rates by adjusting the money supply. For example, to lower interest rates, the central bank can increase the money supply through open market operations, such as buying government bonds. This injects more money into the economy, shifting the money supply curve to the right and lowering the equilibrium interest rate. Conversely, to raise interest rates, the central bank can decrease the money supply by selling government bonds, thereby reducing the amount of money in circulation.

Implications for Monetary Policy

The theory of liquidity preference provides a framework for understanding how monetary policy can be used to stabilize the economy. By manipulating the money supply and influencing interest rates, central banks can affect aggregate demand and economic activity.

During periods of economic recession, when aggregate demand is weak, the central bank can lower interest rates to stimulate borrowing and investment. Lower interest rates make it cheaper for businesses to finance new projects and for consumers to purchase durable goods, such as cars and homes. This increased spending can help to boost economic growth and reduce unemployment. [See also: How Central Banks Control Inflation]

Conversely, during periods of inflation, when aggregate demand is excessive, the central bank can raise interest rates to curb spending and cool down the economy. Higher interest rates make borrowing more expensive, discouraging businesses from investing and consumers from spending. This reduced demand can help to bring inflation under control. However, raising interest rates too aggressively can also risk triggering a recession.

Criticisms and Limitations

While the theory of liquidity preference has been highly influential, it is not without its critics. Some economists argue that the theory oversimplifies the complex relationship between money, interest rates, and economic activity. They contend that other factors, such as fiscal policy, technological innovation, and global economic conditions, also play a significant role in determining interest rates and economic outcomes.

One specific criticism is that the speculative motive for holding money may not be as significant as Keynes initially believed. Empirical evidence suggests that the demand for money is primarily driven by transactional and precautionary motives, rather than speculative considerations. Furthermore, the theory of liquidity preference assumes that the money supply is exogenously determined by the central bank. However, in reality, the money supply can also be influenced by the behavior of commercial banks and the decisions of borrowers and lenders.

Another limitation is that the theory does not fully account for the role of credit markets in determining interest rates. In modern economies, a significant portion of lending and borrowing occurs through credit markets, rather than directly through the money market. The supply and demand for credit, as well as factors such as credit risk and regulatory requirements, can also influence interest rates. [See also: The Role of Credit in Economic Growth]

Contemporary Relevance

Despite its limitations, the theory of liquidity preference remains a valuable tool for understanding the relationship between money, interest rates, and economic activity. It provides a useful framework for analyzing the impact of monetary policy on the economy and for understanding the behavior of financial markets. In particular, the theory highlights the importance of central bank independence and the need for policymakers to carefully consider the potential consequences of their actions.

In recent years, the theory of liquidity preference has gained renewed attention in the context of quantitative easing (QE) and negative interest rate policies. QE involves central banks purchasing large quantities of government bonds and other assets to inject liquidity into the financial system. The goal of QE is to lower long-term interest rates and stimulate economic activity. However, the effectiveness of QE has been debated, with some economists arguing that it has had limited impact on real economic growth. The theory of liquidity preference can help to explain why QE may not always be effective, as it suggests that the demand for money may be relatively insensitive to changes in interest rates when rates are already very low.

Negative interest rate policies, which have been implemented by some central banks in Europe and Japan, involve charging commercial banks a fee for holding reserves at the central bank. The goal of negative interest rates is to encourage banks to lend more money and stimulate economic activity. However, the effectiveness of negative interest rates has also been questioned, with some economists arguing that they can have unintended consequences, such as reducing bank profitability and discouraging saving. The theory of liquidity preference can help to explain why negative interest rates may not always be successful, as it suggests that individuals and businesses may prefer to hold cash rather than invest in assets with negative returns.

Conclusion

The theory of liquidity preference offers a valuable perspective on the determination of interest rates and the role of monetary policy in influencing economic activity. While it has faced criticisms and has limitations, its core principles remain relevant in understanding modern monetary economics. By considering the transactional, precautionary, and speculative motives for holding money, we can better comprehend the complexities of financial markets and the challenges faced by policymakers in managing the economy. As central banks continue to grapple with unconventional monetary policies in a low-interest-rate environment, the insights provided by the theory of liquidity preference will continue to be invaluable.