Unlocking Liquidity Preference: A Comprehensive Guide for Investors

In the dynamic world of finance, understanding the nuances of investor behavior is crucial for making informed decisions. One such concept that significantly influences financial markets is liquidity preference. This article delves into the intricacies of liquidity preference, exploring its definition, key drivers, implications, and relevance for investors and policymakers alike. We aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of this vital economic principle, equipping readers with the knowledge to navigate the complexities of modern financial markets.

What is Liquidity Preference?

Liquidity preference, a cornerstone of Keynesian economics, refers to the demand for holding assets in the form of money rather than illiquid investments or other assets. In essence, it reflects people’s desire to have immediate access to cash. This preference arises from the inherent advantages of holding money, such as its convenience for transactions, its ability to serve as a store of value, and its role as a safe haven during times of uncertainty. John Maynard Keynes introduced this concept in his seminal work, “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money,” highlighting its impact on interest rates and economic activity.

The core idea is that individuals and businesses prefer to hold their wealth in the most liquid form – cash – even if it means forgoing potential returns from investments. This preference is not constant; it fluctuates based on various factors, including interest rates, economic outlook, and individual circumstances. Understanding these fluctuations is key to comprehending market dynamics.

The Three Motives Behind Liquidity Preference

Keynes identified three primary motives that drive liquidity preference:

The Transaction Motive

The transaction motive is the most straightforward. People hold money to facilitate everyday transactions, such as purchasing goods and services. The amount of money held for this purpose depends on income levels and spending habits. Higher income generally leads to increased spending and, consequently, a higher demand for liquidity for transactions. The transaction motive is relatively stable and predictable, closely tied to the level of economic activity.

The Precautionary Motive

The precautionary motive stems from the desire to have a buffer against unexpected expenses or emergencies. Individuals and businesses hold money as a safety net to cover unforeseen circumstances, such as job loss, medical bills, or equipment repairs. The strength of the precautionary motive is influenced by factors such as risk aversion, economic uncertainty, and the availability of credit. During times of economic turmoil, the precautionary motive tends to strengthen as people seek greater financial security.

The Speculative Motive

The speculative motive is perhaps the most intriguing and influential of the three. It arises from the belief that holding money can be advantageous if interest rates are expected to rise or asset prices are expected to fall. Investors may choose to hold cash in anticipation of buying bonds at lower prices or purchasing other assets at discounted rates. This motive is highly sensitive to expectations about future market conditions and can lead to significant shifts in liquidity preference. When investors anticipate a market downturn, they often increase their cash holdings, driving up the demand for liquidity.

Factors Influencing Liquidity Preference

Beyond the three motives identified by Keynes, several other factors can influence liquidity preference:

- Interest Rates: Interest rates are a key determinant of liquidity preference. Higher interest rates make it more attractive to invest in interest-bearing assets, reducing the demand for holding cash. Conversely, lower interest rates diminish the opportunity cost of holding cash, increasing liquidity preference.

- Inflation: Inflation erodes the purchasing power of money, making it less desirable to hold. High inflation typically leads to a decrease in liquidity preference as people seek to invest in assets that can maintain or increase their value.

- Economic Uncertainty: Economic uncertainty, such as recessions or financial crises, tends to increase liquidity preference. During uncertain times, people become more risk-averse and prefer the safety and flexibility of holding cash.

- Financial Innovation: Financial innovations, such as credit cards and online banking, can reduce the demand for holding cash by making it easier to conduct transactions and manage finances.

- Government Policies: Government policies, such as monetary policy and fiscal policy, can influence liquidity preference. For example, expansionary monetary policy, which involves lowering interest rates and increasing the money supply, can decrease liquidity preference.

The Impact of Liquidity Preference on Interest Rates

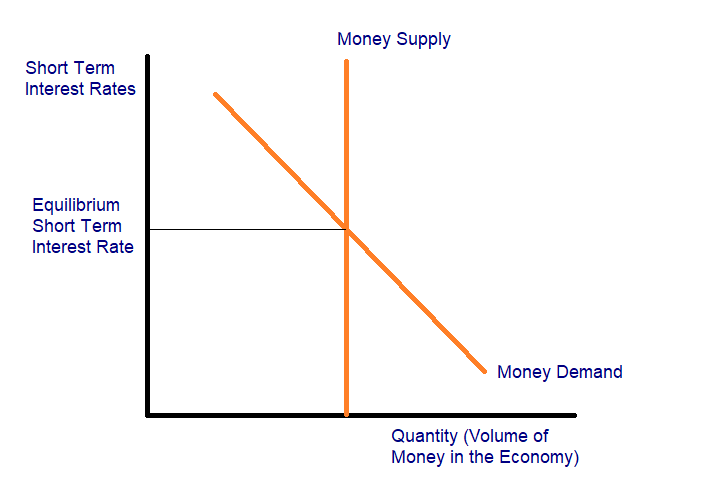

Liquidity preference plays a crucial role in determining interest rates. According to Keynesian theory, the interest rate is the price that equilibrates the supply of money with the demand for money (liquidity preference). When the demand for money increases, interest rates tend to rise, and when the demand for money decreases, interest rates tend to fall. This relationship is fundamental to understanding how monetary policy affects the economy.

Central banks can influence interest rates by controlling the money supply. By increasing the money supply, central banks can lower interest rates, stimulating borrowing and investment. Conversely, by decreasing the money supply, central banks can raise interest rates, curbing inflation and slowing down economic growth. The effectiveness of monetary policy depends, in part, on the sensitivity of liquidity preference to changes in interest rates. If liquidity preference is highly sensitive to interest rates, then small changes in the money supply can have a significant impact on interest rates and economic activity.

Liquidity Preference and the Zero Lower Bound

One of the challenges faced by central banks in recent years is the zero lower bound on interest rates. This refers to the fact that nominal interest rates cannot fall below zero. When interest rates are already near zero, central banks may find it difficult to stimulate the economy further through conventional monetary policy. This is because people may simply choose to hold cash rather than invest in bonds with near-zero returns, a situation known as a liquidity trap. In a liquidity trap, increases in the money supply may not lead to lower interest rates or increased economic activity, as people are content to hoard cash.

To overcome the zero lower bound, some central banks have experimented with unconventional monetary policies, such as quantitative easing (QE) and negative interest rates. QE involves the central bank purchasing assets, such as government bonds, to increase the money supply and lower long-term interest rates. Negative interest rates involve charging banks for holding reserves at the central bank, in an attempt to encourage them to lend more money. The effectiveness of these unconventional policies is still debated, but they represent an attempt to influence liquidity preference and stimulate the economy when conventional monetary policy is constrained.

Implications for Investors

Understanding liquidity preference is essential for investors as it can significantly impact asset prices and investment returns. Here are some key implications:

- Asset Allocation: Investors need to consider their own liquidity preference when making asset allocation decisions. Those with a high liquidity preference may prefer to hold a larger portion of their portfolio in cash or highly liquid assets, even if it means forgoing potential returns.

- Interest Rate Sensitivity: Investors should be aware of the sensitivity of different asset classes to changes in interest rates. Bonds, for example, are typically more sensitive to interest rate changes than stocks. Understanding how liquidity preference affects interest rates can help investors make informed decisions about bond investments.

- Market Timing: Some investors attempt to time the market by anticipating changes in liquidity preference. For example, if an investor believes that liquidity preference is likely to increase due to economic uncertainty, they may choose to reduce their exposure to risky assets and increase their cash holdings.

- Portfolio Diversification: Diversifying a portfolio across different asset classes can help mitigate the risks associated with changes in liquidity preference. By holding a mix of liquid and illiquid assets, investors can balance their desire for liquidity with their need for investment returns.

Real-World Examples of Liquidity Preference in Action

Throughout history, there have been numerous instances where liquidity preference has played a significant role in shaping financial markets and economic outcomes. Here are a few notable examples:

- The Great Depression: During the Great Depression, liquidity preference soared as people lost confidence in the banking system and the economy. This led to a sharp decline in investment and economic activity, exacerbating the crisis.

- The 2008 Financial Crisis: The 2008 financial crisis also saw a surge in liquidity preference as investors fled to safe-haven assets, such as U.S. Treasury bonds. This flight to safety drove down interest rates and contributed to the credit crunch.

- The COVID-19 Pandemic: The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a similar increase in liquidity preference as businesses and individuals hoarded cash to cope with the economic uncertainty. This led to a sharp contraction in economic activity and prompted governments and central banks to implement massive stimulus measures.

Criticisms of Liquidity Preference Theory

While liquidity preference theory is a valuable framework for understanding investor behavior and its impact on financial markets, it is not without its critics. Some economists argue that the theory oversimplifies the motivations behind holding money and that other factors, such as transaction costs and information asymmetries, also play a significant role. Additionally, some critics argue that the theory does not adequately account for the role of expectations in shaping liquidity preference.

Despite these criticisms, liquidity preference theory remains a relevant and influential concept in modern economics. It provides a useful lens through which to analyze investor behavior, interest rate dynamics, and the effectiveness of monetary policy. Understanding the strengths and limitations of the theory is essential for making informed decisions in the complex world of finance.

Conclusion

Liquidity preference is a fundamental concept in economics that sheds light on the demand for holding money and its impact on interest rates and economic activity. By understanding the three motives behind liquidity preference – the transaction motive, the precautionary motive, and the speculative motive – investors and policymakers can gain valuable insights into market dynamics and make more informed decisions. While the theory has its limitations, it remains a valuable tool for analyzing investor behavior and navigating the complexities of modern financial markets. Recognizing the factors that influence liquidity preference, such as interest rates, inflation, economic uncertainty, and government policies, is crucial for understanding how financial markets function and how they respond to economic shocks. Ultimately, a thorough understanding of liquidity preference is an invaluable asset for anyone seeking to succeed in the world of finance. [See also: Understanding Interest Rates] [See also: Monetary Policy and the Economy]